The first ship’s captain I ever encountered was scary. I was 22 years old. My job was crewing cable ships for BT’s marine division. I did something that made the captain angry (I called him on the satellite phone on a matter that, to him, was far too trivial. I didn’t realise satellite calls were very expensive). I’ve probably met a dozen or so captains since then who have mostly been nicer to me, albeit with the authoritative presence necessary for someone in charge of a ship with its crew, guests and cargo, and a thousand things that could easily go wrong.

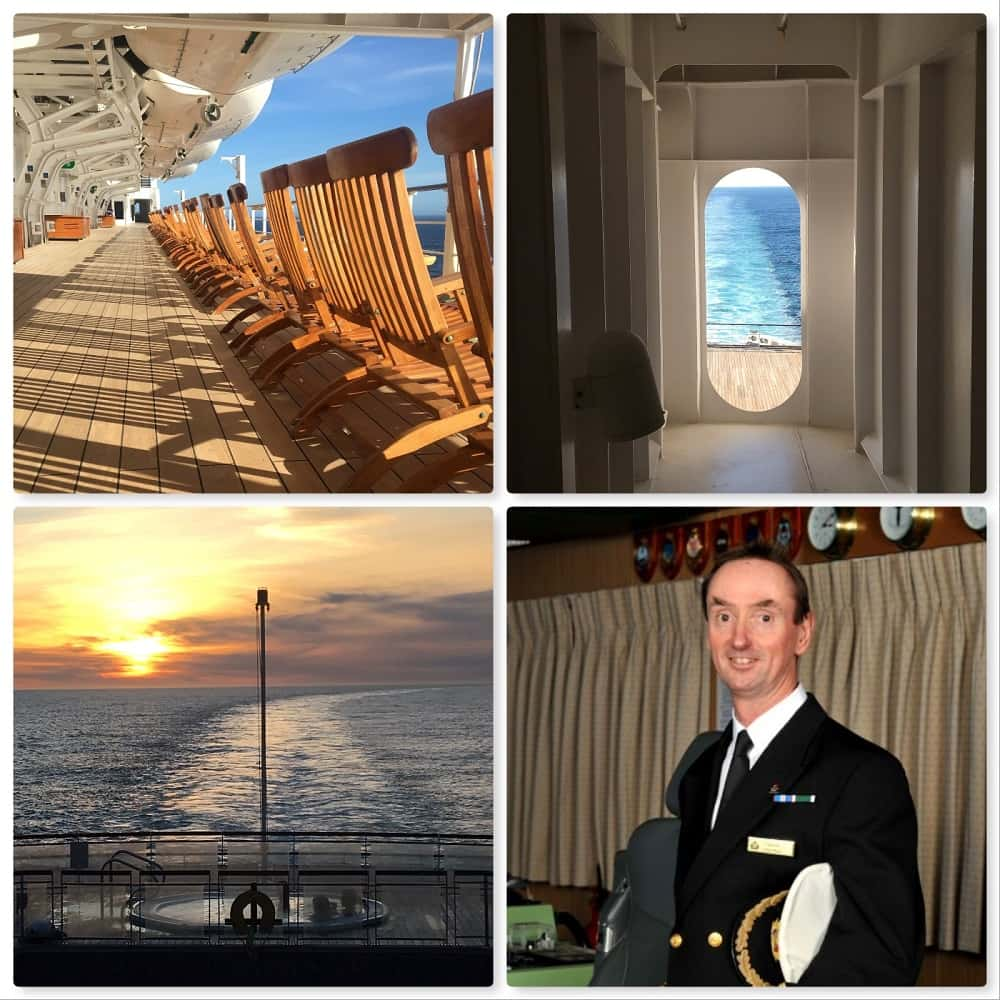

I sailed from New York on the ocean liner, Queen Mary 2, a couple of weeks ago for the inaugural Cheltenham Literature Festival at Sea. My first experience of Captain Christopher Wells was in the guest safety briefing. Over the public address system, with serious voice, he talked about on-board safety and instructed us to attentively watch the crew’s potentially life-saving demonstration. His commanding tone created a sombre mood and, with it, a sense of security.

Later that evening I went to the Remembrance Service, led by the captain. His delivery was again solemn, but quieter, befitting the occasion.

We fast became accustomed to his commentaries at noon every day over the ship’s address system, where he spoke about our location, the sea state and matters of interest (like the fact we were passing over the site of the wreck of the Titanic). I began to notice his strength in engaging people. His humour was starting to emerge in the snippets he shared in these briefings, like the fact that a sea cucumber breathes through its anus!

On a passenger liner, one of the important roles of the captain is that of host. I was interested to see how ours would be in a social environment interacting directly with passengers. He noticed that I was wearing anti-sea-sickness wrist bands and asked me how I was doing with them. He related a story to me about someone else who had been suffering badly with sea sickness until she was given a set of bands by a fellow passenger. This was a quick conversation because others were waiting to speak to him. Even so, he managed to make me feel as though he was interested and cared. He instantly found a way to connect with me and certainly had the adaptability to go from ‘distant captain’ figure to a human being relating to another.

A fellow passenger remarked to me what a personable chap he seemed as well as someone in whose hands one felt safe.

On day five any remaining stereotype of the ‘distant captain’ was well and truly blown.

A performance called Wodehouse at Sea, a specially written piece featuring author Sebastian Faulks, actor Gina Bellman and journalist James Naughtie, took place in the on-board theatre. These professionals of stage, radio and screen were in full flow when suddenly (to our surprise, and possibly to the surprise of those on stage too) the captain himself burst from the wings to let loose his inner thespian.

He seemed to enjoy being on stage and making us laugh, and I think this sealed the liking that many passengers had started to feel for him. He was leading us safely across the Atlantic but was also prepared to have a bit of fun with his guests. I felt he genuinely wanted people to have a good time.

Although I was ostensibly on board the Queen Mary 2 as a guest, the ship’s owner, Cunard, is also my client. I remembered one of my early conversations with them where we talked about what it takes to be a captain in the Cunard fleet. They described to me the important mix of exceptional technical abilities combined with the ability to be a good host. A rare combination, possibly, but essential, to keep everyone safe as well as give them a magical experience.

I always talk to clients about the importance of choosing the right kind of person for the job, not just someone who ticks all the boxes on the CV.

Our captain will surely have ticked all the CV boxes, as there must be few master mariners with the skills and experience to command a ship such as the Queen Mary 2. But what made him the type of person who could captain her were the additional things I saw on the social occasions – his ease of connecting, his sense of fun and his adaptability that meant he could tune into different people quickly.

When you select a person on their strengths you are seeking to understand all their qualities, values and motivations. In other words, you see them as a whole person and then you let them fly. Or in this case, sail.

Sally Bibb is the author of Strengths-based Recruitment and Development, the go-to resource for organisations looking to understand more about the strengths-based approach to recruitment. If you’d like more information about our strengths work, call us on +44 (0) 7721 000095 or email hello@engagingminds.co.uk

Image (on main blog page) of Queen Mary 2 Berthed @ Southampton by Rab Lawrence [CC BY 2.0], original image on Flickr here.